River Time Roundtable Recap

Summary transcript of Atlanta River Time Roundtable, June 14, 2021

Panelist Bios

Jonathon Keats is a globally-renowned conceptual artist and experimental philosopher known for creating large-scale thought experiments. He’s also a journalist – having written for major publications from Wired Magazine to Forbes – and an author of six books. Jonathon was last in Atlanta when Dietz and Keats created a new art movement – Agrifolk Art – in which they equipped fifty Leyland Cypress on a Christmas tree farm to make art and then curated the best of their work, framed it and hung it at a gallery in West Midtown Atlanta. Atlanta River Time is Jonathon’s brainchild and we’re fortunate that he’s chosen Atlanta for this project.

Michael Bettis is programming director with AIR Serenbe. For those of you who don’t know Serenbe – you’re missing out. Serenbe is an idyllic, arts & crafts new urbanism style village in Chattahoochee Hills along the Chattahoochee River just south of Atlanta. Serenbe is a community dedicated to wellness and the arts are an integral part of that. In addition to hosting artists in residence, AIR Serenbe also runs the Filmer program which pairs artists with filmmakers – and it has done so in the case of Atlanta River Time.

Jodi Lox Mansbach is one of our great champions for sustainable and life-affirming placemaking in Atlanta. After earning degrees from Yale and Northwestern and a Masters degree in City and Regional Planning from Georgia Tech, Jodi served as VP, Development and Sustainability at Jamestown where she was instrumental in the success of Ponce City Market and she also helped pioneer the Atlanta City Studio, the City of Atlanta’s first pop-up urban design center. She is co-founder of Chattahoochee NOW - focused on raising awareness and interaction among Atlantans with a 53-mile corridor of the Chattahoochee, from the south end of the National Recreation Area down to Chattahoochee Bend State Park. As the Atlanta River Time project revolves around – and literally within - the Chattahoochee River, Jodi and Chattahoochee NOW have been instrumental in our efforts.

Ryan Gravel is the visionary behind the Atlanta Beltline and the CEO of a number of businesses with cool names like Generator, Elevator and Aftercar – and, perhaps his flagship, SixPitch which is an urban design consultancy that leverages physical infrastructure to shape cultural and economic outcomes that improve the way of life in our cities. Most recently, Ryan has been engaged

Round One: Nature’s Clockworks

Andrew Dietz (moderator and Producer, Atlanta River Time) :

Atlanta is a city that was built around the railroad. In fact, go to the Atlanta History Center and what's front and center in the window, but a train. Trains are linked to time and efficiency and fast pace. And, it seems like that’s how Atlanta likes to be known.

And along with that, we're known as the “city too busy to hate” - we're about movement and speed and getting things done, efficient, mechanistic, Georgia Tech Engineering pragmatists. And businesspeople. The only famous clock in town for decades was attached to our most famous retail establishment in the days before Home Depot – Rich’s Department Store downtown.

But we do have rivers here as well. So, what would happen if we shifted gears from Atlanta as Terminus of trains and speed and business to Atlanta as Confluence of rivers and creativity and time? Jonathan, talk to us about this idea of River Time - where did that came from? Can can put that in a broader context of other time-related projects you've done?

Jonathan Keats:

Thank you for allowing me to be a part of the Atlanta community, at least in proxy and shortly in person. I have been thinking about time for a long time. The interest that I have comes out of an attempt at figuring out how we got from a more sustainable society and world long before I was born to a world today that is on the verge of the sixth mass extinction, that is facing rampant climate change, and has really not yet come to terms with that.

And what I've been really interested in trying to do is to step back and to ask how we got here and whether there might be something more fundamental that we might think about changing. And it seems to me that there is an argument to be made that time is a culprit. Not that time itself is to blame. But how we have used time has resulted in a world becoming increasingly unwieldy and unmanageable. Which is ironic because our attempt to take control of time was really a matter of trying to take control of the world.

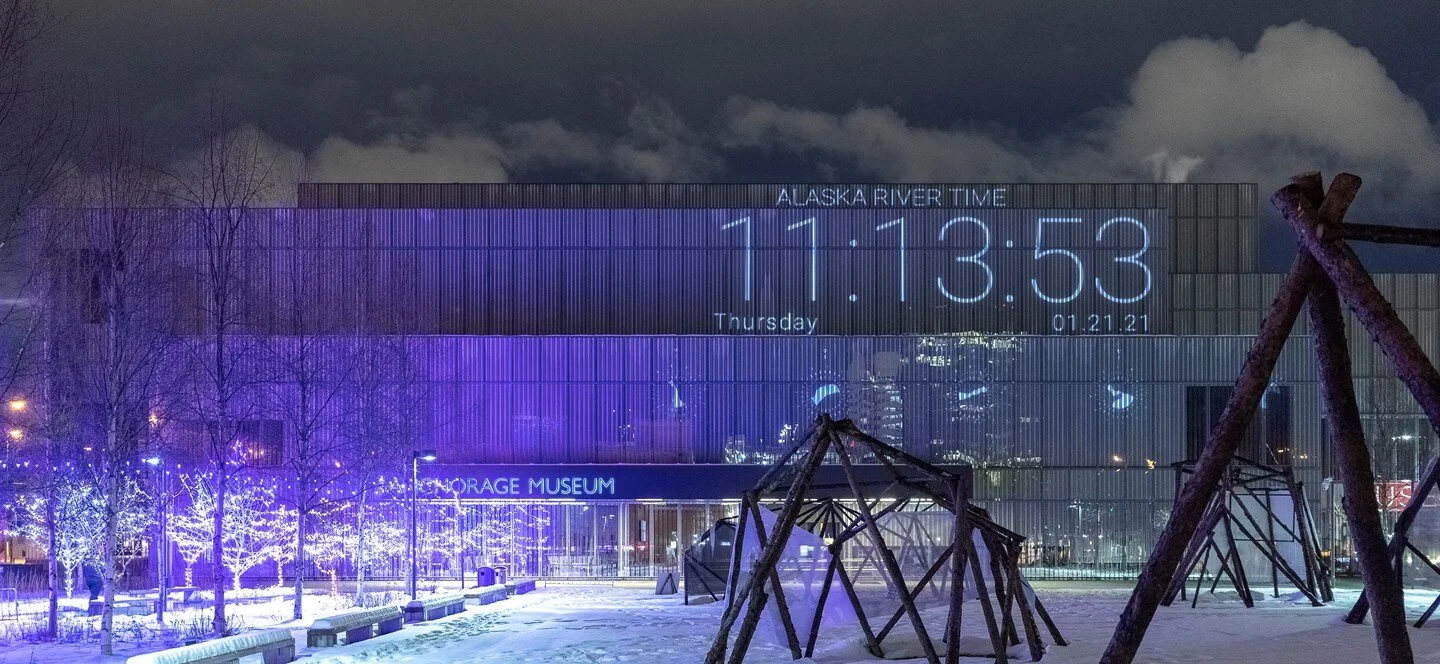

Keats in Anchorage for Alaska River Time (www.alaskarivertime.org) | Photo: Michael Conti

Jonathon Keats:

So by my reckoning, time really gains traction in an industrialized world. With the industrial revolution, and with the rise of the railroads, we went from time as reckoned in the environment to an abstraction, which is, at this stage, based on the pulsation of a caesium atom. And these atomic clocks and the mechanical clocks that preceded them allowed for a disconnect of human society, human civilization from the natural world that allowed for building, allowed for the control of labor forces, that allowed for the rise of globalism and multinational corporations.

And a lot of good came out of that in terms of the fact that we have comfortable lives that probably are a lot more fulfilling in certain ways and certainly a lot easier than in paleolithic times. But nevertheless, there's been a deep cost. And so what I've been trying to do is to figure out what it would take for us to reconnect with time as reckoned before we got ourselves into the current situation.

I started with a cliche because cliches usually have deep truths that they are trying to tell us. And the cliche is that rivers flow and so does time. So I started to think about what would happen if we were to start to pay attention to the flow of rivers and allowed that to be the basis upon which we reckoned time instead of using the abstraction of the caesium atom or of the mechanical clock. What if, instead of overriding the environment, we coordinated with it and connected our actions with the activities of the planet itself and therefore created a feedback loop where the consequences of our actions are manifested not only in the environment, but in time itself as shown through the environment.

Alaska River Time is projected on the facade of the Anchorage Museum. Will any Atlanta institution have the guts to do the same with Atlanta River Time?

Photo: Michael Conti

So you might imagine putting into a river a water wheel that is calibrated at one revolution per minute. And, on the basis of that, you then build a that clock in which the river has authority in telling us what time it is. This is what I've done in Alaska already with a project that I've been working on for the past couple of years. Instead of putting a water wheel literally into the glacier fed rivers around Anchorage, we are using constantly monitored US geological survey data from the rivers as the for a clock that runs more rapidly as flow increases, and more slowly as flow decreases. And a number of things happen as a result of this, one of which is that there are seasonal fluctuations and there always have been.

There's also the stochastic nature of the system. The fact that it is always changing in ways that are fundamentally unpredictable. And then thirdly, there is the long-term trend that in the case of a glacier fed river as a result of climate change, there will be an increase and then a decrease in flow until potentially there's no flow at all. And by the reckoning of River Time, time might just stop.

So what this does potentially is bring two qualities into our everyday lives – it puts what's happening on the river into the vernacular of time and makes it manifest in ways that are immediately recognizable to us. The clock face. The municipal clock we created in Alaska was in the form of projection on the Anchorage Museum. Another way we displayed this time protocol in our everyday lives was by way of a website. This can be a way to bring forward both a sense of the moment and also of unpredictability and contingency - making us more constantly attentive to the environment in which we live. On River Time, we can't plan ahead with hubris. We can't simply assume that everything will work out according to our plans.

Screenshot from alaskarivertime.org | An Atlanta River Time website will launch soon.

So basically what I'm trying to do with River Time is to create a sort of observatory in the form of a clock that allows us to see ourselves through the environment and to calibrate our lives in terms of uncertainty with greater humility, and also in terms of a larger view of the effects our decisions have on that environment.

River Time is ultimately a philosophical proposition or provocation, but it is also a practical attempt at giving people a means by which to enter into a relationship with the landscape. To recognize the fact that we are really a part of nature, not apart from it and to use technology through the creation of a municipal clock in the middle of Atlanta I hope, through various activations on the rivers that bring people to the rivers. Through ways in which people can use this time as a scheduling app, or potentially as we've done in Alaska, that music can be calibrated where there's a metronome that is running on River Time, so you can experience it viscerally or potentially create municipal bonds that might have their interest rate or payout reckoned by the river. All of these can be ways in which to bring River Time into our everyday lives and I'm hoping in Atlanta to do these with all of you.

Andrew Dietz:

Let me interrupt just to note that – looking at the Alaska River Time clock right now - today is July 18th and it’s Sunday for that matter. (actual date of the Roundtable event was Monday, June 14th).

Jonathan Keats:

It has been running for about six months now and as you can see it is both telling you the time of the moment, but also in aggregate. So that date may end up a 100 years ahead or 20 years behind. And what I'm asking people in Alaska to do is to accept River time as an equally legitimate authority. And I'm working now with Earth Law Center on legislation that will recognize River Time as an alternative time standard. Which again, in Atlanta I think would be a really interesting proposition.

Andrew Dietz:

What is it about Atlanta that leads you to think it is an appropriate place for your next iteration of River Time? What do you see doing different here?

Jonathan Keats:

I'm fascinated by the fact that Atlanta is on a river and yet was formed by the railroad. And that the railroad really is the ultimate embodiment of time as controlled by humans. And all of the ways in which in contrast to Alaska - where rivers run through places in a way that people directly, constantly interact with them - in Atlanta from what I've heard the Chattahoochee River, for instance, is somewhat of a mystery.

So I'm interested in how we can use River Time to reactivate the Chattahoochee River and Peachtree Creek, and Atlanta’s other really important waterways in people's everyday lives and how that can potentially change how people look at the landscape and think about ecology.

I don't know that Atlanta is the least likely place to do this, but there is something that is highly unlikely about calibrating time based on a river that is somewhat unknown and unvisited by many. It's kind of the ultimate challenge. And it's a challenge that I think I'm very interested in taking up with Atlantans.

I'm also currently working on River Time in a number of different places that range from Telluride, where the San Miguel River is absolutely central to people's lives running right through the center of town to Vienna where the Danube is legendary and has influence over absolutely every attribute of people's lives.

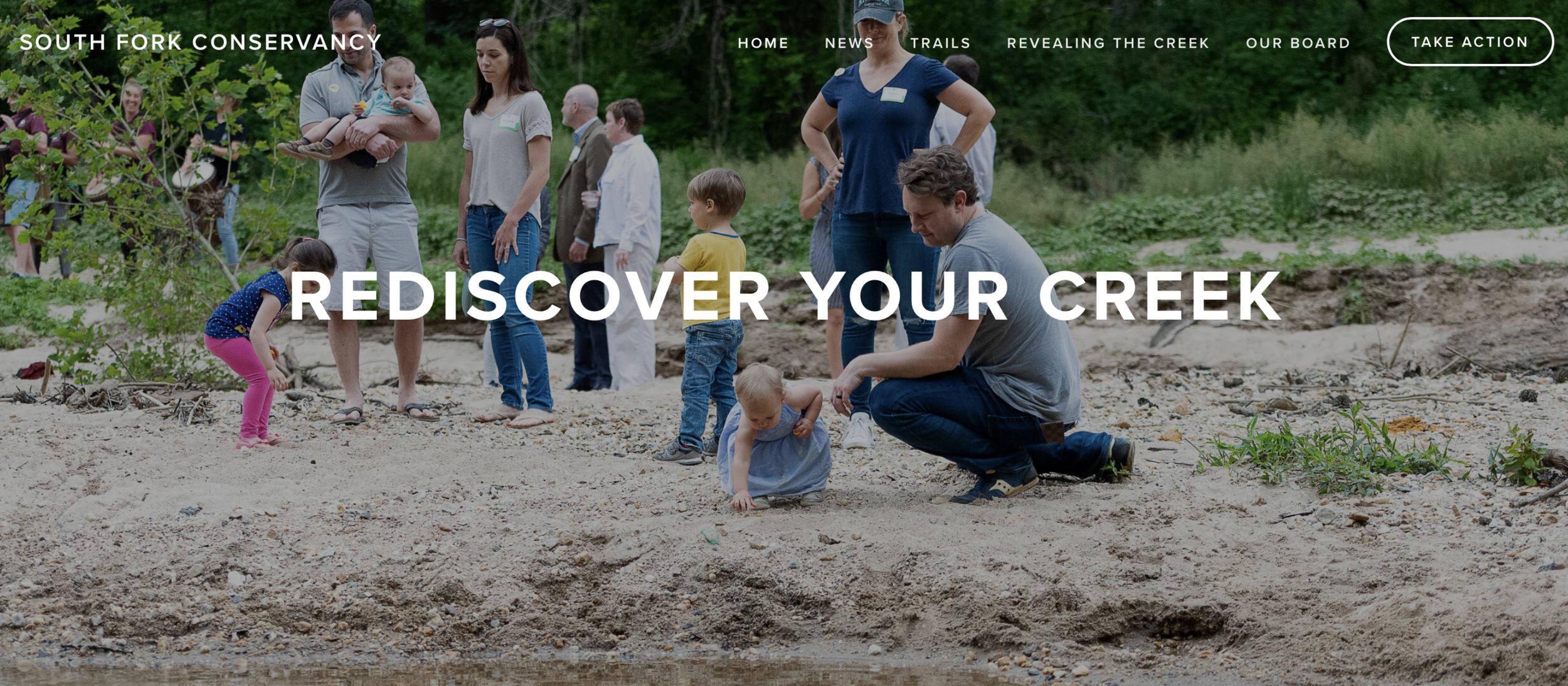

South Fork Conservancy is doing great work to revitalize Peachtree Creek, a major tributary to the Chattahoochee River. See www.southforkconservancy.org

In Atlanta, besides the digital River Time clock, I've been looking at the possibility of using erosion as a way to reckon time. You might imagine stone tablets in Peachtree Creek where you incise dates going forward generationally in increments over a 1,000-year period where the depth to which you cut each date is calibrated by the current average annual flow for the river. Again, as a natural phenomenon, the rate of erosion will be ahead of or behind the predicted rate based on the decisions that we make based on the world in which we live.

River Time can connect Atlanta residents with all the waterways that run through the city, such that people are drawn out to interact with them - literally getting in the water. It's only by interacting with these waterways that we get the sort of visceral connection that will really make change in the world.

Imagine that we can build a municipal River Time clock so that if you want to know what time it is you can go to the middle of town and check the clock. And that becomes a locus for action because it brings people together. You can check your River Time smartwatch if you have one or go online and find out what River Time it is at the website. But more importantly, you can go to the river itself and you can find out in a way that is far more immersive.

Andrew Dietz:

So let me just recap. You're talking about a few different pieces to the Atlanta River Time project. One is the USGS gauging center station sensors as data source for a digital, online River Time clock – maybe project onto the outside of a major Atlanta building. You’re also looking at the possibility of some physical structures in the river such as steppingstones with markings to measure erosion – an erosion calendar. And you’ve talked about possibly a municipal clock for gathering and portraying this data River Time in a central public place. Those are a few of the items on your Atlanta agenda, right?

Jonathan Keats:

Yes. And then also we're going to be running some workshops that will bring people out to Atlanta’s rivers and creeks. And we'll challenge people to make their own River Time almanac as a way in which to reckon time going forward. That will involve making a visit to your local creek every month and making an observation in your almanac where those become calibration points in future years for finding out what month it is. And the River Time month might deviate from the months as told by your wall calendar or by your computer. But those River Time months have a different kind of ground truth to them.

Round Two: River Hide and Seek

Andrew Dietz:

I just want to point out that there's some great chat comments coming up but one of them earlier was “What's the mystery about the Chattahoochee? So, let’s turn for a minute to Jodi. Jodi, I love the front of your Chattahoochee NOW website which says, “Discover our hidden riverfront.” Would you just talk a little bit about Chattahoochee NOW, your interest in the River Time project and maybe answer that question? Probably everybody in today’s session knows there's a river here – more than one, in fact. But not everybody in Atlanta does.

Jodi Mansbach:

Sure. Thanks, Andrew. So Jonathan asks some really deep and some really profound but really fundamental questions about the river. I came to this work by asking a really simplistic question which is where is the river? My story is that I moved to Atlanta 25 years ago from Chicago, where my life was very much oriented at least if not on but by the lake more so than the river. I moved to Midtown Atlanta and I opened a map and saw river on it. And so I did the obvious thing which was to ask people who were from Atlanta where I could go to enjoy and explore that river. And they all pointed me up to the Park Service National Recreation Area, which is a wonderful resource but it's located north of the city and I lived in Midtown.

So I noticed a river that was due west and much closer to where I was living but I consistently got told that I couldn't go to that river. And that stuck in my mind as very strange. The conventional story is that Atlanta is a train city. But, if we trace that back like most cities or settlements, it was actually founded on the river specifically the point of the confluence of Peachtree Creek and the Chattahoochee River. That is the true birthplace of modern Atlanta. It's from that point that the Creeks - the Native Americans - and the European settlers traded at the now famous trading post of Buckhead.

That Atlanta train was initially supposed to be on the river. But it topographically did not work and when the surveyor came he was unable to put it next to the river and the spot that he eventually found to locate the rail was at Terminus. But like most cities, the original settlement for Atlanta was founded on a river.

That question that I had - ”Where is this river and why don't people know about it?” - I took it with me to Georgia Tech where I did graduate school and I asked that very question during my studies. I wanted to look at cities that did not have iconic rivers. Not Vienna or Paris but cities where there were rivers but not iconic ones. I looked at Los Angeles, I looked at Denver and I looked at Dallas. And all of those cities were doing significant things to rediscover their rivers but Atlanta hadn't gotten to that awareness level yet.

I learned some really important things in my research like that a lot of people don't know that the Northwest Boundary of the City of Atlanta is actually the river for eight miles. I learned that from essentially Buckhead down to Chattahoochee Bend State Park, there was only one spot that you could physically go to get on the river. And I already knew that Atlanta was a city defined by cars. And as my friend and hero Ryan Gravel says we need more places defined by nature, not defined by cars.

And from there I co-founded along with Steve Nygren and Walter Brown an organization called Chattahoochee NOW. And we had multiple goals, but first and foremost, it was access and it was equitable access. What does it mean in a Metro area that you can't get to a river for a large percentage of the population? Not surprisingly, it’s the group of citizens with the lowest economic status. What does that mean? And so we asked those questions and I tested my hypothesis by asking people about it one day on the Beltline.

Video plays:

Interviewer: Did you know that Atlanta has a river?

Speaker 1: No.

Speaker 2: I've heard like legends that there's a river in Atlanta. I've never seen it myself. It's like a leprechaun.

Speaker 3: So…maybe? I would say I'm not really sure.

Jodi Mansbach:

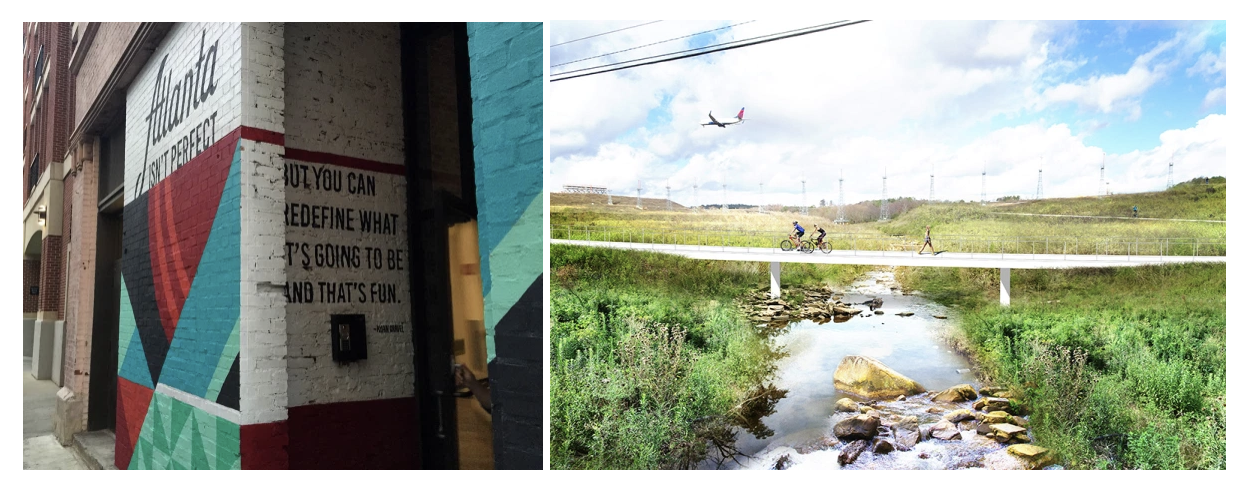

So, along with Ryan and his firm SixPitch, we produced a vision for 53 miles of the Chattahoochee River. And we produced an event called “Where the F is the River?” And that got a lot of attention because people wanted to know. So, we produced a report that talked about this idea about how hard it was to get to the river. There's some good news about this story - some real bright spots. There are some great grassroots work that's been done already by groups like the Riverkeeper and by Groundwork Atlanta and some great work done within the City of Atlanta in getting folks to the river. And most recently there’s been a master plan produced by the Trust for Public Land, the ARC, Cobb County and the City of Atlanta.

Andrew Dietz:

Well thank you for what you're doing and for getting behind Atlanta River Time as well. Jodi has taken us on tours of river highlights across Atlanta and helped Jonathon pick the right places to stage this effort.

Jodi Mansbach:

Because you wouldn't have found them yourself.

Round Three: The Fluvial Beltline

Andrew Dietz:

No. I had no idea. Speaking of things I had no idea about…when Jonathan and I spoke with Ryan Gravel a few weeks back, he told us he was working on a major river project for the South River. And I’m like, where is that? I had no idea that was a river anywhere. I mean no disrespect to the South River I just didn't know it was there. So Ryan, please talk to us about your experience working with these river-related challenges. Tell us what you've been doing, what you're seeing and how you think Atlanta River Time might help?

Ryan Gravel:

Sure. Thanks Andrew. I've been lucky to work on several water infrastructure projects in the region; Most of the major waterways we heard talk of today the Peachtree Creek, the Chattahoochee River and the Flint River. And I’m currently working with the Nature Conservancy on the South River.

If you don't know, Atlanta sits high on the subcontinental divide. So two-thirds of the region drains into the Chattahoochee River and down to the Gulf of Mexico. The rest of the region drains into the South River, which becomes the Ocmulgee and Altamaha and flows to the Atlantic Ocean. That ridge line - that subcontinental divide where the railroads crossed the river - that's why Atlanta is there.

And if you understand the Beltline which is about transportation primarily, but also green space and community development the focus of it isn't the infrastructure – the infrastructure is the tool for accomplishing the goal. The goal is creating the lives that we want to lead. The reason people love the Beltline is because it's making Atlanta into the kind of place they want to live their lives. And so that's the way to think about infrastructure. From my perspective that's the goal of infrastructure. And so water is sort of an obvious form of infrastructure not only because it's necessary but because it has a unique connection to our humanity and our very lives.

Ryan Gravel:

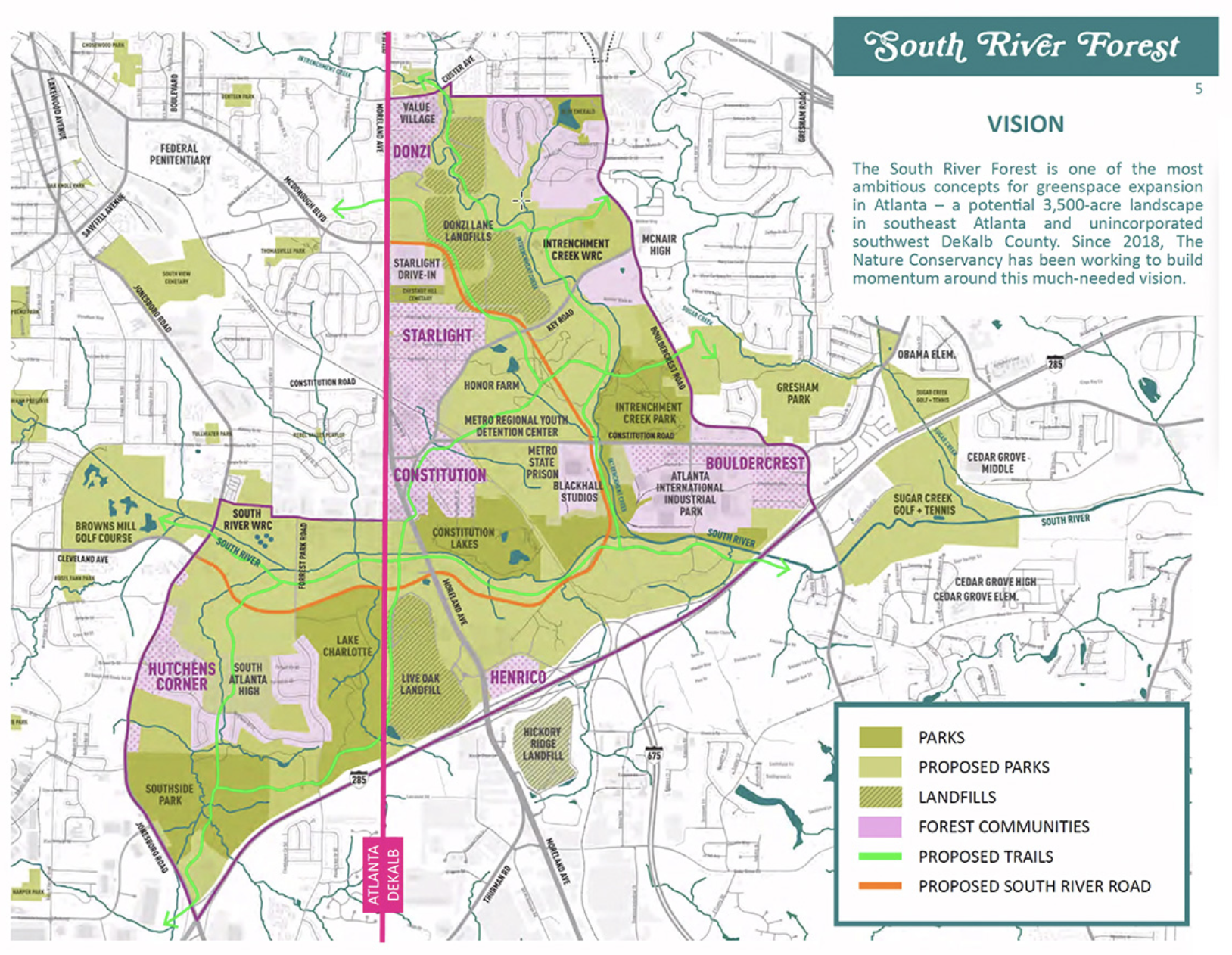

I had a project I was doing with the Atlanta Department of City Planning to imagine how the region is going to change and how we design for that change to grow into the best version of ourselves. And one idea that came out of that was for very large regional park in Southeast Atlanta organized around the South River. It is Metro Atlanta's last chance to have a major forest inside I-285. It's bigger than Stone Mountain Park, but inside 285. The landscape was made up of landfills and truck yards and degraded and there are also some beautiful areas of forest and a handful of parks and the ideas was to craft it into a 3,500-acre landscape. The vision and aspiration is for what that forest can do for us, what kinds of lives this forest could create for us, how it could support the communities that are there now, how it could create ladders of economic opportunity, create spaces for wildness and habitat and all that. And also address water quality and water control kinds of issues headed downstream.

And so we're in the early stages of it. We are in the thick of it. This is early Beltline days. There are a lot of people who don't get it, they don't see it yet. And so we're trying to inspire them and compel them to come to the table and see this big vision. And, unsurprisingly, this area has been a real dumping ground for generations because they're invisible. We don't know them. We don't see them. We ignore them. We bypass them. We bridged over them. Those landscapes are also the front lines for gentrification and change.

Atlanta is going to more than double its population in the next 20 years. The region it's going to grow by 3 million people by 2050. That's like moving Charlotte to Atlanta in 20 years without doing anything about regional transportation. And so the economic pressure that puts on these landscapes in towns and the closer in suburbs of Atlanta that have walk ability that have access to transit that have general proximity to downtown and everything else is really significant. So they're under pressure. And I'm going to share with you one site just so you know if you want to get involved in the South River because I can't help myself because we're in the thick of it.

There's a 340-acre forest owned by the City of Atlanta, but outside the city limits. It's called the Atlanta Prison Farm. It's been proposed to be a park for 25 years and suddenly about a month and a half ago the city announced they're going to build a police training facility there without any public comment. The neighborhood found out about it in the newspaper. The reason they want to put it there is because the neighbors don't have any say. They don't have a voice in City Hall because its unincorporated and they're not city residents so they can't vote for the mayor or the city council. We're trying to stop that. That training facility could be anywhere.

The most immediate thing this week is that Atlanta, the city councils finance executive committee is meeting on Wednesday, they are deciding whether they're going to give a ground lease to the Atlanta Police Foundation. It's the point of no return. If they do it, we've just lost 340 acres of forest. That's the centerpiece for this bigger vision. There are also private landowners, movie studios bulldozing on 150 acres here and there. We've got smaller developers creeping around the edges. If we want to do this, we have to figure it out. And we have to pay for it, it's going to be expensive and it's going to be big but we have to do it because the city is going to change. And if we don't want it to grow into something we don't recognize anymore we want it to grow into the best version of Atlanta that we possibly can imagine.

Round Four: Art and Environment

Andrew Dietz:

Well, we'll be tapping you Ryan, for your brain power on these issues. One thing we do know is that art, whether it's conceptual art like Jonathan does or painting or music or anything like that – art is a great way to raise awareness, to raise communication. And Serenbe is a great example of an area in Greater Atlanta that has used art and culture to connect to the environment. Michael Bettis is with AIR Serenbe. Michael, talk a little bit about what this little village down South of Atlanta is doing with an institute of art culture and the environment and an artist residency program? And why are you getting behind River Time?

Michael Bettis:

Thank you. So Serenbe is a wonderful idyllic community south of Atlanta that exists in a pocket of space that unless you are familiar with it you don't quite know that it's there. When artists would come into residency they think well, I'm about to go out into the middle of nowhere. And then they realize actually, I'm only about 30 minutes to curbside to the airport. And when they arrive in Serenbe and see everything the place offers to them they're even more blown away by the fact that this very intentional Agro-Hood exists in this space so close to the major City of Atlanta.

From Serenbe’s website - The community is in Chattahoochee Hills, near the the River.

It’s a really intentional community that realized pretty close to its inception, the importance of art and its relation to the environment around it. Beginning in about 2007, they formed the Serenbe Institute and their goal as a 501(c)3 nonprofit was to honor the surrounding land and bring arts and culture to this pocket of Chattahoochee Hills. The artist residency formed a couple of years after that and I've now been there for almost five years.

Our artist residency is a sabbatical for creativity. It's a space where people like Jonathan can come and not work on a project like Atlanta River Time. Given our location it almost seemed too good to be true and perfect because we’re so close to the Chattahoochee River and to the City of Atlanta.

And one of the initiatives that AIR Serenbe created in 2017 and revisited this year is Filmer. Where we capture the artists in residence in a short documentary film about their process and person. We document the artists and their process as a way to share with the community at large. This area where we're located in Chattahoochee Hills and South Fulton, doesn't have a lot of arts programming serving this area. The Serenbe Institute, and AIR Serenbe have really taken charge over the years to be sure that both the community of Serenbe and the overall Chattahoochee Hills, South Fulton area are witness to the amazing creators that come from around the country.

We're very excited to be able to capture and nurture these processes and help move them forward. The whole concept of River Time is to understand how we reconnect with time and that's kind of what an artist residency is about as well. It's a chance to reconnect with the time and space to do what otherwise you may not otherwise be able to do.

AIRSerenbe Artist Residences - Rural Studio 20k House Design

Andrew Dietz:

And Michael, before we move on, please tell everyone about the buildings at AIR Serenbe where the artists stay. It's an example of the kind of innovative things you're doing with your facility.

Michael Bettis:

Absolutely. Our two cottages where artists stay were designed by The Rural Studio – the off-campus, design-build program at Auburn University’s School of Architecture. The cottages came out of Rural Studio’s 20K house line. The idea is that a home can be designed and built for $20,000. And so we brought this concept from Hale County in Alabama to Chattahoochee Hills and designed these green, EarthCraft certified buildings for our artists to stay in residence. And ever since we built them in 2016 our program has grown exponentially.

Andrew Dietz:

They're great inside as well. It'll be a great place for Jonathan as he helps us figure out how to make River Time real in Atlanta and the surrounding area. Jonathan will be here from San Francisco in mid-September, but before your Fall visit, we’ll have some additional activities online. Then, we'll be moving to activities by the Chattahoochee and Peachtree Creek such as the almanac workshops Jonathan mentioned. Maybe at Peachtree Creek near Zonolite or at the confluence of the North and South forks of Peachtree Creek as it pokes out from beneath a major highway interchange. And then long-term a vision of maybe erosion calendars in the river, maybe a meander calendar that follows the winding flow of some waterway in and around here. And then ultimately, a public clock tower to rival Rich's clock downtown but based on River Time.

We'd like to introduce you to Jonathan in a broader way. And as part of that we want to make you familiar with the new book chronicling his work to date. Jonathan is incredibly prolific and his body of work so far is covered in this new book, “Thought Experiments” which you can get from Amazon.com. We’re hoping that Jonathon will give a talk about this book for Atlantans sometime soon – stay tuned.

Anne, what else before we wrap up?

Final Bell: What’s Next?

Anne Archer Dennington:

I would just stress that as Jonathan begins his work, The Flux Exchange he’s participating in is really set up as a period of a year or two, when an artist really gets to know our community and we get to know him. He identifies the needs of the community and what's pertinent about this place so he can have an opportunity to filter all of that into his project. So far, because of COVID and everything being online, Jonathan has not had feet on the ground in Atlanta yet. Still, virtually, he’s seen so much and spoken to so many people even though he’s not had the physical experience of being here recently.

So I would say if you to keep up with what's going on with this project you’ll see that we will be doing public programs around his visits, September 14th through 24th, which we imagine as being one of multiple visits he will make to the city over the course of this project. There will be more opportunities to do workshops with him, have coffee with him, have dinner with him, discourse, and to add important elements to Atlanta River Time. To stay in the loop, you can go onto our website, fluxprojects.org sign up to receive our newsletter. You can follow us at Flux Projects online on social media, too.

This is just the very beginning of the conversation, certainly not the end. I don't think any of us could really foretell right now how this project will end up except to say that I feel absolutely certain it will not end up as we all envision at the moment.

Andrew Dietz:

Well, Jonathon, I'm so excited for this project and so grateful that you'll be coming to Atlanta. I truly hope you will give Atlanta’s art and environmental communities a beautifully offbeat, humorous and profound kick in the pants. Thanks to our panelists, Jonathan, Jodi, Ryan, Michael. Thanks again to Flux and our friends at South Fork Conservancy, and thanks to everybody who's joined us today. I look forward to hanging out with you down by the rivers and creeks of Atlanta.

As the Chattahoochee River runs through Atlanta, it is often masked beneath highway overpasses - among other hiding places.